The Taijiquan classics (written by 19th & 20th century masters but credited to earlier apocryphal

persons) refer to the 13 energies of the art.

These are comprised of:

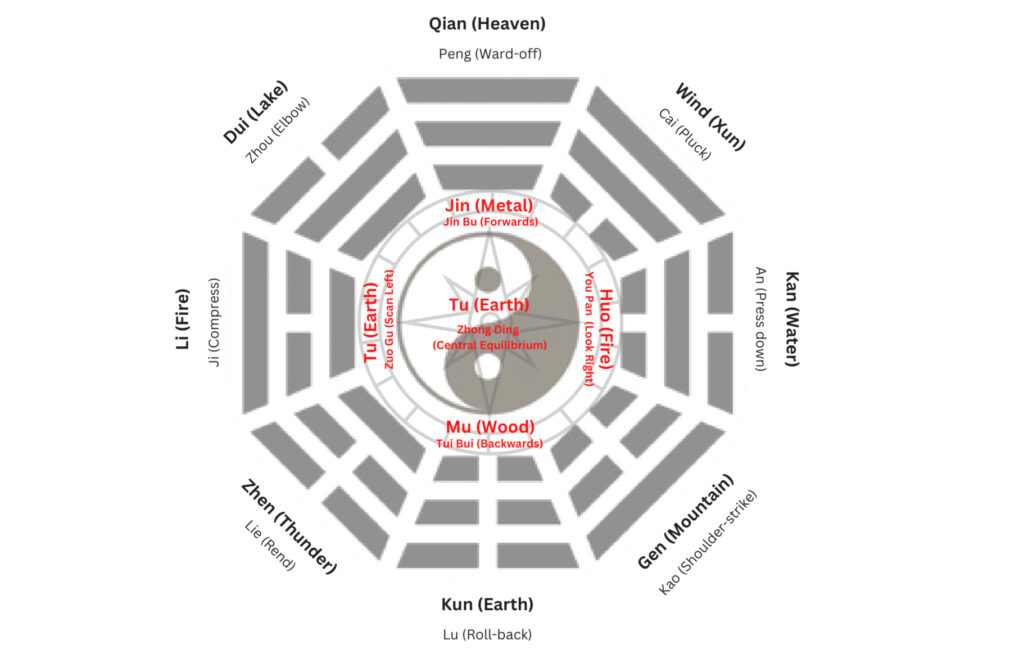

• The 8 methods – Peng, Lu, Ji, An, Cai, Lie, Zhou and Kao

• The 5 directions – Forwards, Backwards, Scan Left, Look Right and Central Equilibrium.

These are often shown as below on a taijitu (yin yang diagram) or onto a bagua, the 8 methods

corresponding to the 8 Trigrams from the Yi Jing, or Book of Changes. Many different theories

have been set forth out on how these each correspond and often the 5 directions are also related

to the 5 elements of traditional Chinese cosmology as well as the cardinal points of the compass.

Stepping back this may appear as a bit of a contrived and clumsy overlay, but one thing that has

always rung 100% true to me is the principle of holding one’s centre. This blog is going to

explore it.

Central equilibrium (Zhong Ding) is different to centre of gravity (Zhong Xin). A centre of gravity is

a physical property of an object, it is a passive thing that changes if the dimensions of the object

are changed. Central equilibrium however is a dynamic active process, one of keeping your

body in an optimally balanced and responsive position.

If, in a static position your centre of gravity has passed over the extremity of your base, then you

have lost your central equilibrium and must by footwork or other means regain it.

It becomes more complicated when you are moving; the Tai Chi classical form and jibengong

should teach you how to practice moving in an optimally balanced way, that is to say without

disturbances to your central equilibrium.

It becomes more complicated again, when you add another body and then that body is seeking to

unbalance you… which is the essence of the Tai Chi tuishou, or pushing hands game.

Maintaining a suspended head top, sinking the Qi, dropping your shoulders, distinguishing

between empty and full in your commitment of weight to either foot, and other admonitions in the

classics serve to create a lowered centre of gravity with the upper body contained in a vertical

zone above it. Not committing too far forwards or backwards or left or right, or leaning over to

these directions makes you more stable for defence and your own attacks.

It stands to reason. If you are leaning or overcommitted in a direction then you must first regain

your central equilibrium before you can change direction and respond to a new threat or change

of direction in your opponent.

Moreover, many of the techniques of Tai Chi seek to use rotation to deliver force or to neutralise

incoming force. This is only possible if you can maintain your central equilibrium, and more; you

need to be aware of where that central axis is located. This is why turning on the weighted foot

has such relevance for those who wish to take their Tai Chi to a martial level of competence.

Watch Judo new beginners at their randori practice stooped over, staring at each others feet and

stiff-arming each other defensively. This limited strategy only works against people with no or

little skill. Contrast that with the top level players in a Judo Grand Slam or Olympic Judo and

especially with how the best Japanese judoka execute their techniques…

They know where their axis is! They know Judo is also about central equilibrium.

10th Dan Judo legend Mifune Kyuzo, often referred to as “the God of Judo” wrote in his book The

Canon of Judo,

“To apply a throwing technique, you must break the opponent’s balance so that he cannot

support his centre of gravity. Kuzushi (unbalancing) is the basis of all throwing techniques and

grappling techniques.”

He goes on to describe this Kuzushi, methods for breaking your opponent’s balance, and

defending against such. To summarise his classic work; Judo, the soft way, will not work unless

your opponent is first unbalanced. He also looks at 8 directions, but without any of the high-brow

metaphysics! In fact, Mifune doesn’t depart from Newton and stays firmly within the arena of

breaking another human’s balance while maintaining your own.

But all of this isn’t just for fighting…. ask a yogi how to sit, or a pianist how to sit, ask a singer

how to stand or a ballroom dancer how to hold your posture. You will find this to be a common

thread. We are at our optimum for stillness and movement with an upright spine, and suspended

head-top pretty much identical to that advocated in Tai Chi and in other methods like Pilates and

Alexander Technique.

An upright skeleton enables you to change direction, it facilitates optimal breathing, it enables the

muscles of your body to relax so that your movement becomes more energy efficient.

From a health perspective, learning to maintain central equilibrium as you move will make you

much less likely to suffer falls, help you to breathe properly and help to release tension in your

muscles.

Moreover, together with the qigong breathing work and the principle of Song, central equilibrium

may help you to heal a lot more than just your body. Increasing evidence suggests that we can

carry the memory of past traumas in our soft tissue. Our muscles, tendons, ligaments and the

fascia that connect it all to our skeletons and wrap us up, can often hold the memory of the

shapes we make with our bodies.

It is highly improbable that you are not, as a human being, carrying some emotional or

psychological hurt that is not impacting directly and indirectly on the balance of your physiology.

By regularly practising an art that inculcates central equilibrium, our muscles can relax, and as the

law of homeostasis demands, your body will get on with the process of healing itself unimpeded,

by letting go of the tension.

Central equilibrium also makes for an excellent strategy outside of martial and health arts.

Keeping yourself together and not allowing circumstances to knock you off balance is important

in business and relationships.

Ever said something you didn’t mean when you were angry, or drunk? Ever got carried away and

bought something you didn’t need? Acting when you are off balance rarely ends well except by

luck!

Being properly in control of yourself before speaking and acting underpins the whole of Chinese

philosophy, from Daoism’s Wu Wei to Confucianism’s Doctrine of the Mean… and has obvious

parallels in Western Stoicism.