“And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul.”

Genesis chapter 2 verse 7:

Qi 气 is understood as many things. Its first literal linguistic and physical meaning refers to air or breath. It has a slightly obscure meaning in Daoism which refers to the pull in nature of forces between polarities, and another more commonplace and popular derived meaning as Energy or Life Force. It has even found its way into the Oxford English Dictionary and onto our Scrabble boards as such!

The “Chi” in the name “Tai Chi” is a totally different Chi (極) which understandably seems to get quite a few beginners in a muddle. In the modern hanyu pinyin romanisation of Mandarin this 極 is now romanised as Ji, so we should really be calling it Taiji, or Taijiquan, but especially in the west we have persisted with the older Wade-Giles romanisation of Chi, which is the source of this confusion.

So what is Qi?

In my view no English word can capture successfully the breadth of meanings of 气.

Interestingly however, we can see strong parallels in meaning between Qi and spirare, the Latin verb to breathe, from whence are derived inspire, expire, respire and the noun spiritus. When we die, we expire, both literally as the breath leaves, but also figuratively as the spirit exits the body. Obviously, to our ancestors as to ourselves, irrespective of culture, we observe that pretty much anything alive demonstrates that it is so by breathing. Adherents of western scientific theory would agree that living animals and vegetables alike are actively engaged in gaseous exchange.

First responders to a medical emergency are taught to check first the state of the following in a casualty:

A – Airway

B – Breathing

C – Circulation

If a person can’t respire, and isn’t respiring, then the priority is to restore that function to save their life.

Similarly the related Greek word pneuma, from which is derived pneumatic and pneumonia also carries multiple meanings, of life, force and breath.

If we accept pneuma or spirare as approximate translations, then all meanings are able to combine; Qi at once refers to the spirit that animates us and also to the principal activity that designates the presence of life: breathing. Qi does not need to be a discreet substance or element; were that the case, it must surely be oxygen… or carbon dioxide if you happen to be a plant!

So this should be it, riddle solved… but somewhat unhelpfully, Chinese Medicine has gone and changed its views on Qi!

Originally Qi entered through the nose and mouth down into the lungs and circulated to the organs and tissues of the body via the arteries (the cardiovascular system).

Thus it appears in the Huangdineijing of the Warring States Period, but by the time we get to the Han Dynasty we have Qi being transported via meridians rather than by the blood.

A century earlier, west of the Gobi the great Roman philosopher, dramatist and politician Seneca (c. 4 BC – 65 CE), wrote in his Questiones Naturales, “our bodies are irrigated by both blood and breath, which passes along channels of its own.”

Seneca’s idea of breath flowing through its own channels is a similar assumption to that ascribed to the Chinese physician 華佗 Hua Tuo (c. 140–208 CE) who proposed the idea of meridians. This might strike us as coincidence, an almost inevitable result of logical inference, or a potential ancient cross-pollination of ideas between west and east.

Today, in the standardised Beijing medical texts of the mid-20th Century, Qi has become seen as a sort of bio-electricity transported around the body via the meridian system so familiar to modern acupuncture practitioners.

If you were looking for a clear explanation within modern traditional Chinese Medicine for Qi you will probably be a bit disappointed. I have read articles which assert that Qi is analogous to the bioelectric signals of the nervous system. I have read other articles highlighting the highly conductive nature of the body’s fascia, advancing the idea that meridians were ahead of their time and some that even claim to have discovered acu-points or meridian channels within the fascia. Disappointingly, few of these are peer reviewed and most are widely and accurately disparaged as pseudo-science.

Similarly within Tai Chi and other traditional Chinese, Japanese and Korean arts, many practitioners also make reference to this Qi, Chi or Ki. Some incorporate breathing work (Qigong or Chi Kung) into their syllabus, some use it as an esoteric principle to describe the inner workings of their art. Historically, in Qing Dynasty China, whence most of the extant traditional Chinese martial arts originate, most martial artists accepted Qi as a legitimate physical property of the body. They probably did so because most historical martial artists were much less educated than doctors, and they had no basis or alternative model of physiology with which to challenge the accepted wisdoms of a 2,000 year old medical tradition.

Given this backdrop, it is very difficult to understand whether older original martial arts texts are referring to energy or breath when the character is used because in many cases they quite simply could have been meaning either! If you are not 100% certain of the context then you have to either hazard a guess, or keep an open mind and bring two possible explanations with you into your practice!

Here’s an example:

When Yang Chengfu wrote “Sink the Qi”, what did he mean?

Sink the breath?

Sink the energy? If so, what energy and how?

The advantage of adopting an open mind to practise rather than discarding reason like a cult devotee, means that you can draw your own conclusions experientially. Breathing down into your diaphragm rather than raising up your chest and shoulder muscles is not only superior for gaseous exchange, but also helps you to maintain a sunk centre of gravity, and a relaxed structure without the rising and falling of chest breathing. If he was meaning to keep your weight sunk through intention, then we arrive at the same or a similar result.

Let’s take a look now at the etymology of the character Qi 气 in our quest for its meaning.

I know some people prefer to use the traditional character 氣 , which has Mi 米 the character for uncooked rice underneath it, the idea being that it symbolises steam rising from a bowl of rice… and so many of you have probably been told Qi can’t just mean air or breath but must mean energy, because of the rice bowl.

You might also be aware of the separate Daoist character 炁 with its own distinct meanings and context, further muddying the waters and the obfuscating the definition struggling to take shape in your mind. Especially as it is a homonym so some people will probably have used these characters interchangeably for a good thousand years.

However, most people don’t know that the traditional character didn’t have the bowl of rice originally. The modern simplified character 气 is actually a lot closer to the original Shang Dynasty (c. 1600 BC– c. 1045 BC) oracle bones script, with its three simple straight horizontal lines arranged vertically.

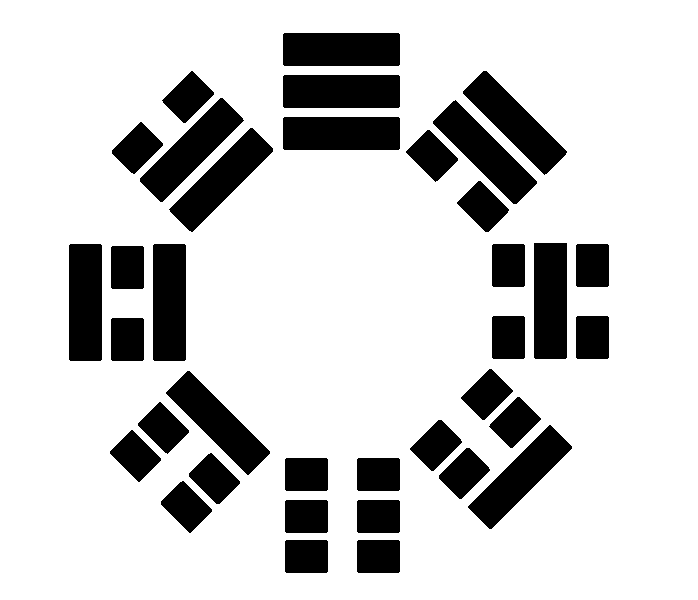

These three lines are sometimes said to pictographically represent layers of clouds, evoking the feeling of the sky. Some of you might have already noticed that this early version of the character for Qi is almost exactly the same as one of the Ba Gua (8 Trigrams) in the Yi Jing (Book of Changes).

Qian 乾; This is the top trigram of three full lines which denotes simultaneously the male Divine Principle, the Creative Element Itself, Heaven, Tian, 天, the Yang Polarity, the Sky Father…

Are we then looking at a coincidence? I think not.

What better way to depict the air, and life giving breath, than this?

The character 气 seemingly then has its origins in a symbol and name for God probably older than Yahweh.

Thus the etymology of the character seems to indicate that the meaning of Qi may always have been intended to encompass the simple breath, as a common noun and mundane verb, and at once also the very Breath of God, of Heaven, that animates all things.

Just a suggestion, but perhaps we glimpse here in the linguistics, a remnant of an ancient religion that underpins all medicine and philosophy… It is patently absurd to suppose the ancients had conceptualised bio-electricity before the end of the Shang Dynasty.

Instead of overreaching into faith beliefs and invisible elixir fields and meridians we have yet to find (in spite of millennia of meticulously dissecting cadavers for traces them), let us pause and take a deep breath.

Perhaps we have been looking too hard, and we just need to breathe, saturating our bodies and minds with the life-giving Qi, until we glimpse that beautiful horrid truth, that each Breath itself is the gift of Life that accompanies each of us from our arrival to our departure without need for further elaboration.

“Then shall the dust return unto the Earth as it was, and the spirit return unto God who gave it.”

Ecclesiastes 12 v7 And in the meantime, “Just breathe motherfuckers!” Wim Hoff